FREE! Subscribe to News Fetch, THE daily wine industry briefing - Click Here

![Banner_Xpur_160x600---Wine-Industry-Insight[63]](/wp-content/uploads/Banner_Xpur_160x600-Wine-Industry-Insight63.jpg) |

ALSO SPONSORED BY:

Wine Industry Insight |

|

The Path To Netflix-Quality Wine Recommendations Leads Through The Doors of Perception

Articles in this series include:

-

Article #1: How A Netflix-Style Recommender Is Vital to Reversing Wine’s Market Marginalization

-

Article #2: Why solving the “Paradox of Choice” is a major reason Netflix’s recommender is worth $1 Bil/yr. And why wine fails at that.

-

Article #3: Reviews and 5-Star ratings are so useless for recommendations that Netflix ditched its prized $1-million algorithm.

-

Article #4: Wine profile matching fails because genes determine that no two people taste the same wine the same way.

-

Article #5: Netflix Added Big Data To Amp Up Recommendations. Why Wine Needs a Touch of That Too.

-

Article #6: The Path To Netflix-Quality Wine Recommendations Leads Through The Doors of Perception

This series has been examining the substantial evidence of why wine recommendations and reviews fail. One of the big reasons is because no two people taste the same wine the same way. However, wine’s recommendation attempts are immensely more complicated because your brain handles scent perception in a radically different way than any of the other senses.

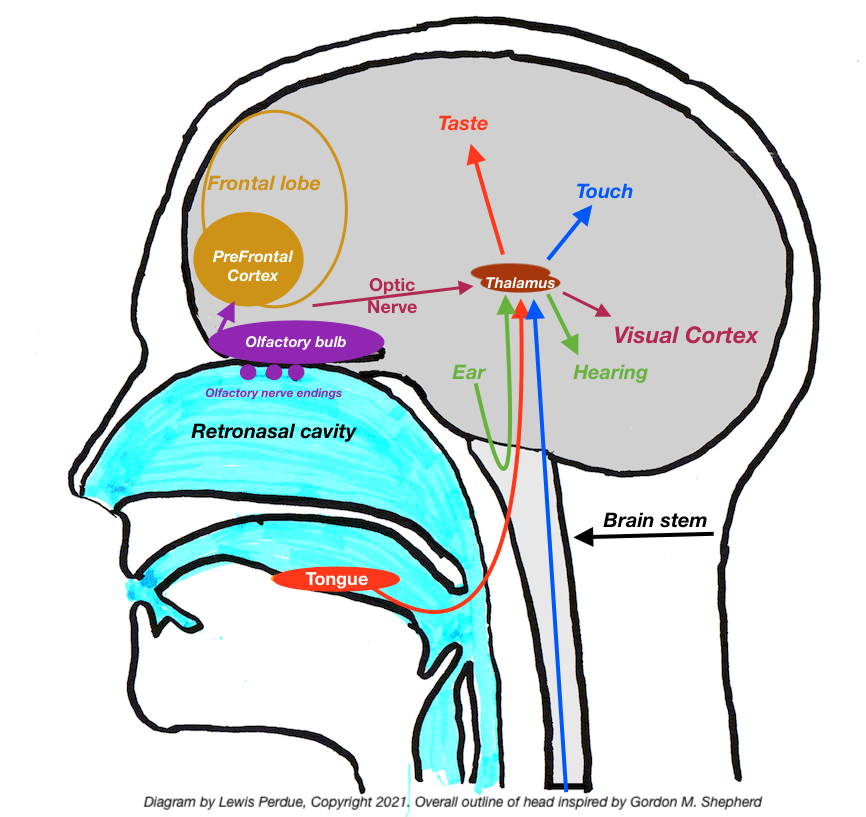

Unlike sight, sound, taste, and touch, your brain gives odors immediate, direct, hardwired access to the PreFrontal Cortex (PFC) which is responsible for the highest levels of thought and reasoning. The PFC is the structure that makes us human … and determines why you are you.

In addition , odors — olfactory signals — are the most complicated, numerous, confusing, and ineffable of all senses. Not coincidentally, they are virtually impossible for individuals to describe.

This means that wine recommendations cannot access the core advantages that have made Netflix’s algorithms and methods a billion-dollar success.

Netflix has a massive and seemingly impossible advantage over wine because it deals with sight and sound rather than smell and taste. To understand that, we need to look at the metrics of senses, and the way the brain handles them — especially the lavish celebrity concierge treatment offered to smells.

First, the Metrics

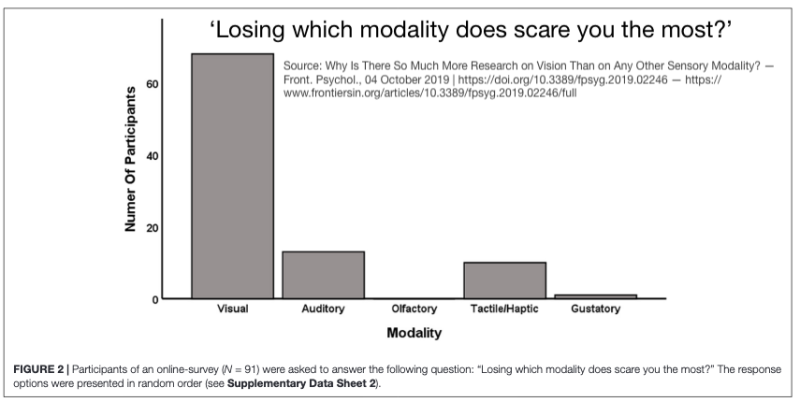

Netflix’s recommendation advantages are not surprising given that most people consider vision and hearing as the most vital of all senses.

This chart (above) is confirmed by an even more recent study, and may be a source of the commonly cited (but totally unconfirmed) unproven assertion that eighty percent of our perception, learning, cognition and activities are mediated at least to some extent through vision.”

However powerful that sight and sound may be, those two senses operate in the brain with remarkably simple and straightforward manners, in contrast with the enormously complicated systems of smell and taste.

A brief look at the metrics of these four senses offers important insights into why Netflix has it easy.

METRICS: Sight/Vision

Four types of vision sensors:

Rods to detect light level and three different cones to detect red, green or blue. (Ever wonder why the LEDs in your television screen are red, green and blue? Now you know.)

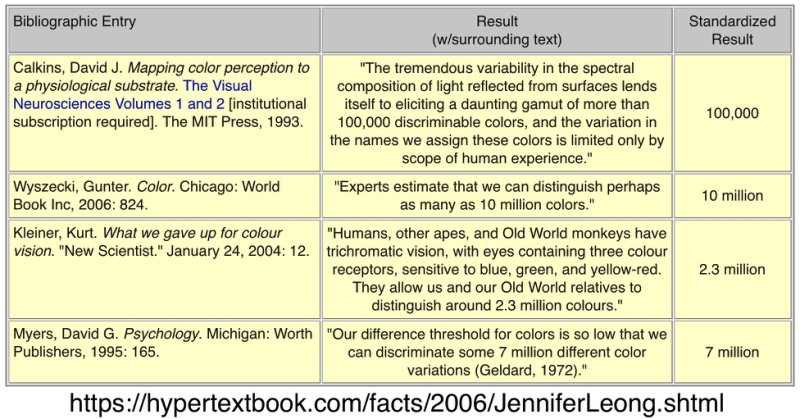

The number of colors a person can see varies widely, but tops out at about 7 million.

Standard tests for vision create standards for focus (20/20 vision, color detection, and ability to detect brightness. Those indicate a relatively narrow range of “normality.”

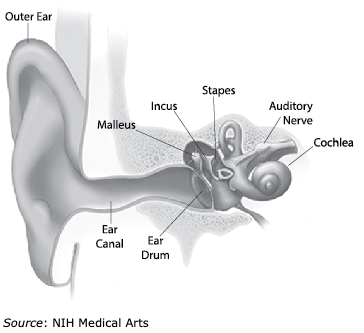

METRICS: Hearing

Hearing relies on two kinds of sensory cells.

Standard hearing tests for the ability to hear pitch and amplitude of sounds confirm the fairly narrow range of “normal.” There is actually a definition for “20/20 hearing.”

METRICS SUMMARY: Vision & Hearing

- Vision: 4 types of receptor cells.

- Hearing: 2 Types of auditory receptors.

Smell/Olfactory Problem: We don’t have a trillion words.

There are 400 types of olfactory receptors, and the scientific research so far indicates that no two people are likely to have the same exact set. That means that there are approximately 4.71238 possible combinations of olfactory receptors.

Looked at another way, there are 4.71 Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion ,Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion, Trillion individual ways of smelling.

That number far exceeds the approximately 110 billion people who have ever lived on earth as estimated by the Population Reference Bureau

Image source: Population Reference Bureau

In addition, this article from the journal Science indicates that the 400 active olfactory receptors in the average person enables each human to discriminate more than 1 trillion different scents.

Source: Science

But we don’t have a trillion words to describe scents. This is a problem for people trying to describe olfactory sensations to other people given the fact that the average vocabulary is 20,000 to 35,000 words.

Not having a trillion words for odors is the least of the olfactory issues because major study noted that people can identify only two or three scents in a complex mixture. That study held serious implications for substances such as wine which are mixtures of hundreds of taste and smell compounds when it concluded that,

“…subjects encountered substantial difficulties with more complex mixtures with only two components being identified in the four- to six-component mixtures. In general, tastes were more easily identified than smells and were the only stimuli identified in the five- to six-component mixtures.”

That ability has a substantial genetic component which has also been demonstrated in twin studies.

Taste/Gustatory

It is not surprising that tastes are more easily identified than scents given that only six human basic tastes exist (counting fat which is now considered as a 2015 addition to the original five: Bitter, Sweet, Sour, Salty, Umami, Fat. (See: Oleogustus: The Unique Taste of Fat)

Vision and hearing = safety & well-being

Vision and hearing have most likely prevailed as today’s dominant senses because long-ago humans and other creatures with inadequacies in those two senses most likely never lived long enough to reproduce and remain in the gene pool. In addition to immediate threats to survival, absent or inadequate vision and hearing meant a decreased or absent ability to communicate with other humans, resulting in decreased societal support.

For more on this, click: Vision and hearing = shared perceptual communication (the Netflix advantage)

The radical way your brain processes smells makes describing them and creating recommendations from them almost impossible

Indeed, olfactory signals occupy an extremely high brain priority level that surpass all other senses in its speed and direct priority access to the PreFrontal Cortex –– the center of human thought and perception.

Understanding this requires a brief trip through how the brain is put together. While the following journey is a bit like a biology class, even if you don’t absorb every point, it’s needed in order to provide an important data point on just how complicated it is to try and rely upon taste and smell as checkpoints on the road to useful recommendations.

In First Class Seating: Olfactory by itself. All Others in Tourist

While taste, vision, hearing, and touch nerve impulses all travel first to the brain stem and then to the thalamus, olfactory signals skip that connection and take a privileged express route to the highest levels of brain function that makes each of us who we are as individuals and as human beings.

Everybody But Odors Must Detour To The Thalamus For a Delay And Directions

The thalamus is a two-lobed brain structure about 5.7 centimeters long, located above the brain stem. It evaluates, sorts and routes signals to the appropriate sensory parts of the brain which further processes each type of sensory data (except olfactory).

The thalamus also plays roles in involved in learning, memory, perception, consciousness, the regulation of sleep and more.

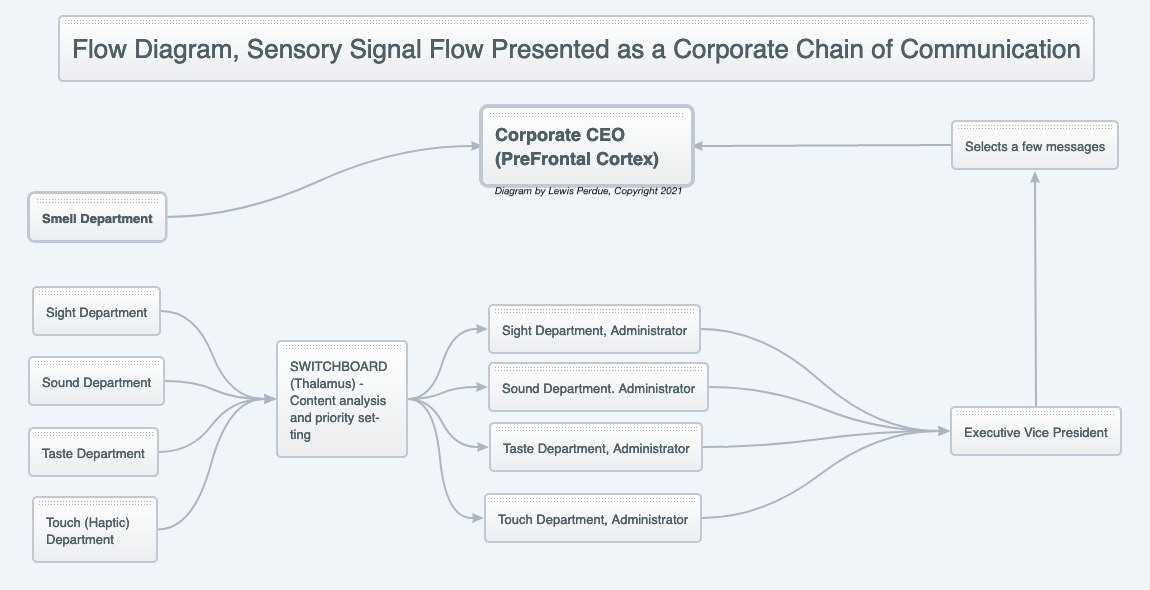

Look at this in a more familiar way: A corporate hierarchy

Think of sensory receptors as communication workers performing specific tasks outside the lobby of the different departments of an information factory:

- Sight Department

- Sound Department

- Touch (Haptic) Department

- Taste Department

- Olfactory Department

In departments 1-4, data messages are sent to a central switchboard (thalamus) which looks at each sensory data message (impulses).

After reading the messages from Departments 1-4, the thalamus analyzes them for content and priority and forwards them on to the relevant (senses 1-4) Department Administrator.

The Department Administrator of each department further analyzes the message content (edited and annotated by the thalamus) and sends some of the messages to the Corporate Executive Vice President residing on specific brain’s frontal lobe.

The Corporate EVP will send some of the most immediately important of these sensory data messages to the CEO (Pre Frontal Cortex) where the CEO may initiate perception, trigger memories, activate motions like deciding whether Fight is better than Flight (or vice versa).

This message journey takes many neurons, inches, and time.

Significantly, the PFC is the neural center of everything that makes you human, determines your personality — in other words, everything that makes you, you.

And the Olfactory department?

Direct access to the CEO. No delays, no interim edits.

Just bare-handed nerve cells with one end located exposed in a retronasal patch and the other end attached to a brain structure called the olfactory bulb at the top of your nasal cavity. The olfactory bulb then sends the sensory data directly to the CEO. The journey takes a couple of inches and arrives with express speed.

In other words, olfactory sits in a privileged position with immediate, direct, unedited priority access to the most important part of your brain…while other scents take a somewhat bureaucratic journey first.

Smell gets primo access to the brain regions that make us who we are as humans

Regardless of how you look at it olfactory signals go straight to the top.

As for other sensory signals, they lag behind. Eventually, the thalamus processes taste, sight, sound and touch signals and sends them to specialized regions of the brain designed to handle each specific sense. Eventually, each sensory region routes some of the signals to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and other parts of the frontal lobes that sit right behind our foreheads.

What Makes the PreFrontal Cortex So Important?

Understanding the enormous importance of the PFC shows just how elevated and privileged the olfactory sense is.

Among the numerous vital functions performed by the PFC are

- voluntary movements (deciding how and when to move),

- sequencing of complex or multi-step movements, such as getting dressed or making a cup of tea,

- speech and language production in the dominant frontal lobe (opposite your dominant hand),

- attention and concentration,

- working memory, which involves processing recently acquired information

- reasoning and judgment,

- organization and planning,

- problem-solving,

- regulation of emotions and mood, including reading the emotions of others

- personality expression,

- motivation, including evaluating rewards, pleasure, and happiness,

- impulse control,

- controlling social behaviors.

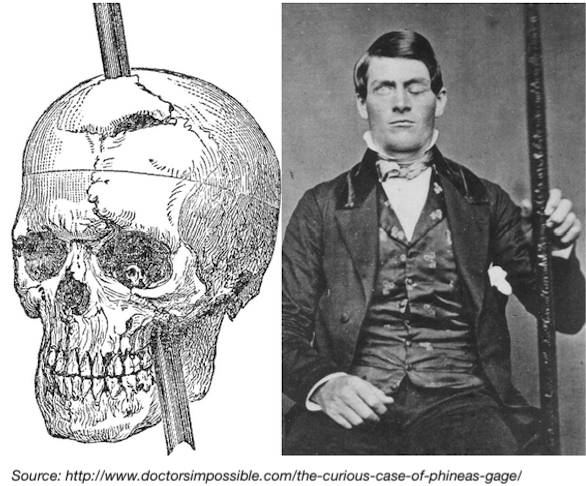

Knowledge from Misfortune

How do we know just how important the PreFrontal Cortex is?

Much of the knowledge about the pivotal role of the PFC comes from observing changes caused by diseases and injuries.

One of those observations dramatically illustrated how the PFC shapes the human personality and many other substantial and fundamental attributes to what makes an individual who they are.

Left image recreated after Gage’s death shows damage. Photo is of Gage posing with the pike that had been blasted through his head.,

The PFC’s role in making us human was revealed in 1848 following an industrial accident in Vermont.

In that accident, Phineas Gage, a twenty-five-year-old railroad construction foreman began his day as a man known by his employers, coworkers, friends, and family unanimously as an intelligent, responsible, honest, polite, disciplined—moral —man.

Then late that hot summer afternoon, Gage made a near-fatal mistake as he used a four-foot steel pike to tamp explosives into a drilled rock hole. The powder exploded, driving the steel pike into his left cheek, through his eye socket, and the frontal lobes before shooting out the top of his head.

Astonishingly, Gage recovered — remarkable given the state of medical care at the time. After his recovery, doctors found his raw intelligence and physical abilities unaffected and no physical incapacitation other than losing his left eye.

But the steel pike had changed his entire personality. Instead of the former Sunday-school teacher, the physically healed body housed a profane, venal, violent brute with no self-control or sense of responsibility.

Decades of scientific and medical study of the case concluded that the change had come from damage to his PFC: Gage had become a victim of his new biological configuration. The ‘bad’ Gage had evicted the ‘good’ Gage.”

Further investigation for the curious can be found at the the following links:

Easily accessible:

More technical:

- Opening the “Black Box”: Functions of the Frontal Lobes and Their Implications for Sociology

- Insights into Human Behavior from Lesions to the Prefrontal Cortex

The most non-technical, approachable and comprehensive body of work can be found in the books and writings of the late neurologist Oliver Sacks whose classic book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat explores the issues in a manner accessible to all.

How? Why?

How and why is it that only the sense of smell has a sleek, stripped down receptor system that plays a key role in odor’s short, express, privileged access to the highest levels of thought?

For one thing, the prefrontal cortex is the key area of the brain that involves attention, assesses danger, summons intent and commitment. But why not sight or sound which are also valuable danger senses?

Clearly, no one can say for sure, but one prominent theory is that olfactory cells are the developmental progeny descended from single-celled or primitive organisms that developed a survival mechanism to detect and avoid harmful chemicals.

Related to that theory is the fact that — unlike other senses which have a receptor cell attached to a nerve cell — olfactory receptors are actually naked nerve cells with one end exposed to the top of your nasal cavity and the other end attached to the olfactory bulb nestled close to the PFC.

Sniff and survive

The olfactory neurons with their naked tails wagging in the back of your throat, may be the adapted progeny of some ancestral organisms. One factor supporting this is the presence of odor aversions that don’t have to be learned, but are already built into the PFCs of newborn babies.

Neither adults or newborns need to learn that mercaptan (added to natural gas for safety reasons) stinks. The same goes for many other scents such as those those from sewage and decomposing flesh.

This may account for why olfactory neurons get privileged access to your PFC which can quickly activate critical thinking, memory, decision making, and threat analysis. The faster these can be assessed and reacted to, the better the chances of survival.

But more than for survival, the olfactory sense’s preferential access to the PFC offers the ability to assess a trillion odors, ansd differentiate them at a very deep psychological and emotional level concerning people, food, physical environments and more.

What does this have to do with why it’s so hard describing scents and using those words in reviews and for recommendations??

The PFC connects scents with memories regardless of whether they are pleasurable, stinky, harmless or deadly. Sometimes scents recall memories and vice versa that can be consciously connected. But odor/emotion associations may simply recall emotions — good or bad — that could influence an opinion about wine.

What’s more, some smells are subconsciously perceived. They are odors that can’t have a name, but they have their own real effects on perception and behavior, choices, preferences and and aversions.

A gut feeling

A “gut feeling” may be a reaction to scents (conscious and/or subconscious) detected and forwarded to the PFC so it can tap into memories and other information that create a physiological reaction.

This is an area that leads wine into the “big question” at the intersection of neurobiology and philosophy: where does consciousness come from?

No one knows. Chances are no one ever will. Theories and gargantuan debates abound, but they evade rigorous study.

However research indicates that the PFC, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and other regions in the brain are involved with consciousness and perception, but how and why no one really knows.

Digging Deeper Into Consciousness

In the event that digging into the olfactory sense’s special treatment in the brain, you can always see how quickly it is to get lost in consciousness.

A variety of relatively approachable links are here:

- A little history goes a long way toward understanding why we study consciousness the way we do today

- The Neuroscience of Consciousness

- Are There Levels of Consciousness?

Two bottomless holes are here:

- Google: Where does conscious come from?

- Google Scholar: Where does consciousness come from?

Vision and hearing = shared perceptual communication (the Netflix advantage)

In addition to safety considerations, proper vision and hearing are fundamental in communication that promotes education, personal relationships, the development of society which includes shared perceptions of music, movies and more.

Watching a movie also means that people experience the same sound and visual experience.

This is especially true of those in a movie theater, or who watch the same video with friends/family in the same place at the same time. While there us is no way to determine if each person has the same internal conscious experience, people nevertheless share a common experience — seeing and hearing the same images and hearing the same words and sounds.

There’s common agreement among viewers watching the same video at the same time that actor #1 said the same words, that she jumped out of the same castle window and landed in the same moat filled with alligators.

Viewers don’t have to agree on whether they liked the scene, or the movie, but there’s no doubt that their ears and eyes senses experienced the same thing.

Imagine, however, that — like a movie reviewer — you have written an accurate and detailed review of a movie. The reader of that review will interpret your words according to their own life experience, education and sensory history. That means those readers will also have no perception of the music, body language, the specific scenery, the energy, and raw emotion among the characters or their expressions and tones of voices that convey more than mere words possibly could.

However the fact that movie-goers experience the same sound and visual experience of a film, felt the emotions at the precise same time develop more complete perceptions that — while not identical among all individuals — creates the possibility of a shared understanding.

Taste of course is fairly easy to communicate given the small number of basic tastes. (six).

This is particularly true because most people cannot name more than two or three odors in a mixture. Those who can do that are exceptional. On the other hand, those who are not exceptional in this sense are probably just making it up, guessing and showing off.

Current wine rating, review, and recommendation systems border on fatal irrelevance because flavor (taste + smell) perceptions are completely internal consciousness experiences, and — unlike sight and sound — cannot be shared directly with other people.

As a result, flavor experiences must use words to describe the sensations. Unfortunately, words are enemies of understanding when it comes to describing flavor.

Words can mean different things to different people. What does “complex” mean? Or “balanced?” “Big?” “Olive-tinged black currant?”

ORANGE!

Life experience shapes our tastes, and especially as to how we perceive them.

Perhaps someone says they detect notes of orange.

Are they thinking Mandarin, Navel, Blood, Valencia, Jaffa, or another of the hundreds of types of oranges? All have subtle differences, and the memory of the flavor is inextricably linked with previous experience.

Individual perception exists in the individual brain and is inaccessible beyond the individual skull. As a result, there is no way to determine if two people are talking about the same perception.

While that one flavor may exist in the same perception neighborhood in two people, there is no guarantee that two people will be in the same neighborhood after sampling a simultaneous sip of the hundreds of flavor compounds found in wine.

Substitute any other flavor for orange and the same situation exists … multiplied by all of wine’s flavors.

To some extent, wine experts can calibrate their palates with each other during a tasting where the experienced flavors are named and discussed. And while all may agree on orange, and use it in a calibrated way in a tasting note, there is no way to assure that consumers who read that note will perceive the orange “note” that was described.

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’ ” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’ ”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument’,” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

— From Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass

WE ARE ALL ALICE

We are all Alice looking at wine through a curious looking glass that filters meaning and misunderstanding through the lenses of:

- education,

- culture,

- life experience,

- health,

- context

- environment,

- psychology,

- genetics and,

- vocabulary.

A CONSPIRACY OF WORDS

All those factors conspire to make word choice and meaning as variable a target as individual taste.

“It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is. If the — if he — if ‘is’ means is and never has been, that is not — that is one thing. If it means there is none, that was a completely true statement.” President Bill Clinton, 1998 Grand Jury Testimony in the Monica Lewinsky case.

Context, environment and psychology obviously influenced Bill Clinton’s recursive, existential riff on the meaning of “is.” But similar factors play out in more prosaic communication contexts:

- everyday conversations,

- flat-pack assembly instructions,

- employer directions to workers,

- school and college lectures,

- instructions for installing O-rings in space shuttle rockets and handling deadly viruses at CDC labs.

That’s why tasting notes can make for good reading — interesting, entertaining and funny — but fail more often than not as reliable ways to find wines one will enjoy.

Words and descriptions are enjoyable (and should continue), but are rarely meaningful enough for satisfying purchase decisions.

An article published in The Journal of Wine Economics by Princeton University economics professor, Richard E. Quandt — On Wine Bullshit — offers a far harsher view. The author, also designed computer software that would autonomously write wine reviews from a “vocabulary of bullshit” he compiled.

Of course, one never knows if Quandt may have had a BS epiphany if he had seen the guide to wine descriptions published by Wine Folly. Or whether he would have felt his scatological approbation had been justified.

THE GENETICS OF EXPRESSION

In addition to perceiving the same flavors and smells differently, genetics along with education and experience also gifts some people with better abilities to connect specific names to smells and tastes.

GENERAL, SPECIFIC, VERY SPECIFIC

Vocabulary — the product of education and experience — can also send easily misinterpreted data.

In the example above, assume the first taster has difficulty pinning down the right word for what they tasted. Instead of “grapefruit” they might just state that it had “citrusy” flavors.

That general description would be of no help to someone who hates the taste of grapefruit.

Let’s also think of the second person who hates grapefruit, but is experienced enough to know that comes from fusel oil. Their very specific description might skip over grapefruit and name fusel oil instead.

That very specific description (fusel oil) would be useless to the first grapefruit hater.

The number of ways that descriptions can sabotage understanding probably approaches infinity.

Fruity. Tropical Fruit. Cattley Guava

Tart. Citrus. Buddha’s Hand Citron

Which is “right?” They all are … but most notably to the taster who chose the words.

I have witnessed professional wine writers, sommeliers and MWs debate the identity of a smell and, sometimes, come to no consensus at all. Granted they are a lot better than the average person. Regardless of that ability, their perception — like all perceptions — is personal and does not necessarily translate accurately to other people.

For a real-life test that I use in most every university course I have ever taught in writing or business management, see: “How Big Is A Dog?”

WINE WRITING IS HARD, CAN BE TEDIOUS

Wine writing is hard.

Nailing down a specific taste or smell to an analogous real-world object requires good writing, astute perception and the ability to summon the right word.

The similarity of many wines, especially within a specific varietal (and cornered by the prevailing style of the day) can cause a vocabulary crisis.

Good writers know that maintaining user interest requires more change-ups than a major league pitcher. The same words, over and over, loses readers just like the same pitch produces home runs.

Because of this, there exists a “thesaurus writer, “always searching for different words to describe two near-identical wines. Two different descriptions of virtually the same wine does not help wine lovers choose a wine.

And, in the end, descriptions like “flinty overtones of dried cranberries in a dusty tobacco pouch” may be a good test of the wine writer’s vocabulary, but meaninglessly overwrought prose for the wine consumer.

“I really draw the line at scorched earth and spicy earth,”

“First, I have never eaten earth (although I have smelled earth after a good summer rain) and I have never been near scorched earth, perhaps because Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan were a bit before my time.

“And how do you know what spicy earth tastes or smells like? I could go into my back yard and sprinkle some cumin, cardamom, turmeric and fenugreek; but how would I know that those are the right choices, rather than coriander, chili powder, caraway seeds and cayenne?”

— From On Wine Bullshit

AGGREGATION AGGRAVATION

Significantly, the aggregation of scores or hundreds or even thousands of descriptions of the same wine from different people does not solve the problem. Lots of dirty data does not add up to clean data.

It is conceivable that aggregation combined with some form of analysis of the text might be useful if it retains only the words that all (or most) of the reviews agree upon.

OF ALMOND PASTE AND FLYING ROACHES

Psychology and life experience shade words in individual ways.

In particular, smells connected with a specific memory can exert powerful effects, both psychologically and physiologically. Scientists called this the “Proust phenomenon.”

These smell-evoked autobiographic memories color emotions, but can also have measurable physical effects on the body. (See further reading at the bottom of this article.) Even smell/memory connections that can be remembered only dimly, can influence word choices and even wine preferences and ratings.

A personal anecdote offers an illustration. When I was 10 or 11, my family lived in a house on the Mississippi Gulf Coast a hundred feet or so from the beach. Like most everyone in this warm, humid region, our house would occasionally host giant flying roaches the size of your index finger. Genteel language referred to these tiny flying monkeys as “Palmetto bugs.”

While anti-aircraft missiles would have been appropriate, I settled for using a fly swatter. And when I squashed one, they gave off an intensely unpleasant and unforgettable odor.

The memory came back with a stomach-turning shock years later, when being served a warm croissant filled with almond paste. I immediately recalled the freshly dead bugs. Quickly made an excuse to leave the table. (“Sorry, just remembered that I left my cat in the dryer.”)

It took me decades to get over that memory connection and learn to love almonds, almond croissants, marzipan and the like. But, until that time, that smell aroused unpleasant memories and emotions.

In addition to these remembered smell experiences, extensive medical research has shown that the foods and liquids that a pregnant mother consumes can alter their child’s taste preferences for a lifetime.

Whether we are aware of them or not, smells do connect to memories that can influence moods and word choices in our speech and writing. We can compensate for those we are most aware of, but not those that rest beneath the surface.

Further Reading

Psychological and physiological responses to odor-evoked autobiographic memory.

Brain–Immune Interaction Accompanying Odor-Evoked Autobiographic Memory

The Nose, an Emotional Time Machine